(After)

Curator: Hadas Maor

22/12/2005 -

22/04/2006

The last part of the twentieth century was characterized by simultaneous development in various theoretical disciplines that sought to diagnose some moment of annihilation indicated in the various fields of life and practice, and to touch upon some fundamental, radical change in the perception of the subject, the world, and the totality of their possible interrelations. Analysis of the structure and status of the subject, with its diverse manifestations, was, thus, a key concern to a group of scholars from various discursive fields, among them Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault, Jacques Lacan, Jacques Derrida, Jean Baudrillard, and others.

The concept of the ‘death of the subject’ was introduced by Fredric Jameson in the early 1990s in his seminal essay Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, where he explored the waning of historicity in contemporary culture, the growing depthlessness, and the fundamental change that occurred in the emotional constitution of the subject in society, while linking all these to the structure of the new economic world system – globalization – which was, in his perception, one of the major causes for the very emergence of these changes. For Jameson, postmodern culture is an expression of the structure of the new economic system, a system whose predominant formal feature is depthlessness, and where the aesthetic production is combined with the general production of commodities.

Somewhat earlier, Jean Baudrillard introduced an in-depth discussion of the basic concepts of ‘original’ and ‘copy’ in his essay The Precession of the Simulacra, describing a situation where the ongoing race for the production of the ‘real’ spawns countless imaginary substitutes that function as ‘hyperreality’, attempting to compensate for the eternal loss of reality. In the era of ‘hyperreality’, as Baudrillard dubbed it, nothing is left of the ‘real’, and a series of copies without an original (‘simulacra’) is created in its stead.

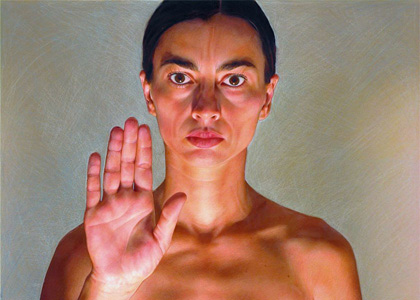

In the period following the ‘death of the subject’, and in the gap that developed as part of the struggle to decipher the definition of the ‘real’, this exhibition sets out to trace the status of the contemporary subject vis-à-vis the complexity of social structures and the intensity of the new power systems within which he must function at the beginning of the third millennium. While doing so, the exhibition also refers to concepts such as center, periphery, and globalization, by examining various cultural situations and focusing on the subject’s position and functioning within them.

The exhibition does not seek to outline and anchor a new principal structural argument with regard to the subject’s status or the various power systems in which he must function, but to offer a spectrum of thematic and visual reflections resulting from the very reference to these notions, while drawing attention to their inevitable intricacy and stratification.

The formulation of the exhibition’s theme and the selection of artists and works included in it, are based on an attempt to characterize the cultural situation as a whole, and on examination of the artists’ works from within and in relation to that situation. At the same time, however, the exhibition may also be regarded as a type of hybrid, striving to dialectically combine the illusion of independent, authentic existence (of the subject in general and the artist in particular) with the inability to evade the boundaries of possibility typical of the political, economic and cultural circumstances of the period, any period, in which the artist lives and works.

The deliberate avoidance of unequivocal or declarative definitions regarding the state of affairs is immanent to the mindset and mode of thinking underlying and resulting from this exhibition. Accordingly, the exhibition avoids explicit reference to possible futuristic and apocalyptic aspects involved in the accelerated technological development and issues such as cloning, genetic engineering, or robotics.

In some respect the exhibition strives to indicate the subject’s place as a site of struggle. A Sisyphean struggle for survival that transpires cyclically and infinitely despite, and perhaps because of, the different forces directly and indirectly threatening to restrict, govern, and annul its scope of existence, thought and action over the years. By focusing on threshold and ambiguous situations the exhibition endeavors to signify a type of collective state of in-betweenness, without engaging in ideological, value-minded judgment of this state, what preceded it and what is to follow it in the future. Or, to borrow Jameson’s own assertion (with regard to capitalism), and the words of Marx before him: ” to think this development positively and negatively all at once