Antimatter

Curator: Irit Carmon Popper

22/09/2011 -

19/11/2011

“The drawing itself, the line. […] We must not limit it, let it be what it will be, all the sensations, all the hues. If it wishes, let it outline itself in space; if it wishes, let it connect deep in the soul. Let us not limit it, it is the truth, the line.” — Aviva Uri1

The exhibition “Antimatter,” the second in the series “Continuum: Installations following the Collection,” consists, like the previous one, of two site-specific installations—a spatial installation and a ceiling installation—which respond to the Museum’s art collection. Iva Kafri’s and Orly Sever’s works delve into abstract formal values as they relate to the sculptural object. Their installations are characterized by images of mirroring, reflection, and replication, calling to mind such notions as reproduction, simulation, simulacrum, multi-dimensionality, and stratification. The exhibition is further supplemented by a quintessential local context which stems from the incorporation of the Israeli art works from the Museum’s original collection in the installations, and from their location adjacent to Yad Labanim’s commemoration space.

Orly Sever refers, as a point of departure, to 1970s wood and iron sculpture inspired by the world of flora and fauna.* The presence of the vegetal organic forms in the metallic substance implies vitality vis-à-vis the death and bereavement. The wooden sculptures were obtained through an act of carving, thus preserving the material’s inner texture, inspired by medieval techniques, popular art, and European modernist sculpture. In the local context, they originate in early Eretz-Israeli sculpture; this sculptural style was pushed to the margins of the mainstream which adhered to abstraction—a perception on which the artist herself was raised and whose values she has adopted in her work.

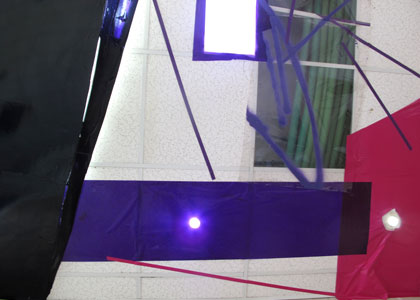

Entering Sever’s installation, one encounters a black wall, the sole remnant of a structure; the sculptures are revealed behind it, on black shelves which appear to float in the space, as if they were leftovers of furniture in a ruined domestic interior.** As a reflection of these works, plaster sculptures created by Sever are installed underneath. Rather than exact replicas, they offer a free, wild translation.2 Original and reproduction, object and its shadow, conscious and subconscious, being and void are situated one atop the other, like a visual realization of the Lacanian transition from the symbolic order of language, logic, and law to the real order which defies both representation and symbolization. The Real—as a crude, threatening aspect of existence—confronts us with the “impossible,” eliciting nightmares or trauma.3

A black horizontal line runs like a thread through the space, generating a dim sense of a water line—a natural element which undermines the exclusive contexts of culture represented in the installation and its setting, in the very act of sculpture, as in the act of commemoration. The dark apocalyptic environment engulfs the viewer with silence; it inspires a sense of termination, of the realms of anxiety innate to human existence, without defined contexts, in affinity with Slavoj Žižek’s declaration of “the true catastrophe already is this life under the shadow of the permanent threat of catastrophe.”4 The dark monochromatic color has a twofold function of containment and suffocation, an expression of an archetypical struggle between belonging and differentiation often addressed in the artist’s works.

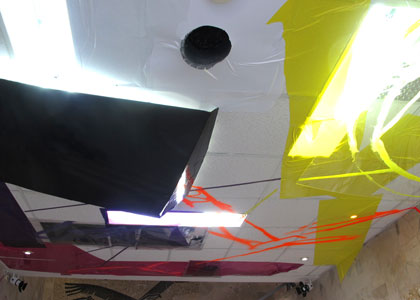

Iva Kafri’s ceiling installation*** is situated above Mordechai Gumpel’s mosaic walls from the mid-1960s.**** Inspired by these works, the installation freely paraphrases their monochromatic cubes. The composition, obtained via a painterly language of line and stain, oscillates between a minimalistic linear gesture and an outburst of expressivity. The colorful geometric forms cut and glued with deliberate sloppiness, are made of paper, cardboard, and Perspex in different degrees of thickness and transparency, offering an echo or a current interpretation of the archetypical natural images embedded in the mosaic, primarily the sun and the bird of prey. The installation elicits a sense of freshness and optimism, corresponding with Zionist utopism and the spirit of heroism. The vivid coloration refers us to Fauvist painting which made a blatant, “beastly” use of color in the early 20th century, opting for the appearance of an unfinished sketch, similar to Kafri who chose to avoid a smooth finish to preserve the sense of process and infuse the works with a human vulnerability, as she attests.

This ceiling work continues the artist’s engagement with the transition from traditional painting to painterly expansion in the space, in a time- and context-dependent process. Among her sources of inspiration, one may name Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbau in the 1920s, as a Dadaist environment in which one could walk, which ultimately led to Action Painting, as well as the environments and happenings in 1950s New York, many of whose participants were painters who sought new modes of expression and stretched the boundaries of the painterly medium.

The title of the exhibition, “Antimatter,” was borrowed from physics, concurrently alluding to art, mainly local art, in the context of conceptualism, abstraction, and the so-called “want of matter.” All the matter in the universe has its antimatter, an antithetical twin or a mirror image. While they resemble one another in behavior and qualities, they have opposite electric charges. Their encounter sets a process of annihilation in motion which leads to discharge of energy. The installations may be construed as visual and material expressions of this phenomenon, because while wandering in the exhibition a passage is created in which—in the wake of the aforesaid annihilation—an energetic outburst occurs and a revival is produced. The dichotomous relationship between matter and antimatter is associated with the interrelations between the original and its image, reality and reflection, real and imagined. It conjures up Walter Benjamin’s assertion about the waning of the artwork’s aura and uniqueness in favor of reproduction loss of authenticity which stands for truth or reality. This idea is teamed with the current changes in the perception of time and space, and the multi-dimensional, simultaneous manner in which we experience reality. This process also recalls Jean Baudrillard’s argument concerning the new semiotic order in which the ability to distinguish between reality and its representation is lost, and consequently, the images representing reality in fact become reality itself.5

Notes

1. Aviva Uri, “The Line,” in cat. Perspectives on Israeli Art of the Seventies: The Boundaries of Languages, ed.: Mordechai Omer, trans. Richard Flantz (Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 2008), p. 574.

2. Gideon Ofrat likens the act of bringing works up from the Museum’s storage space into the exhibition halls to a psychoanalytical process. The museum stores—the repressed materials of the museum’s memory—surf in an exceptional act from “the dark depths of the subconscious” to the halls of “consciousness.” In the transition to the exhibition space, history is created—the beginning of processes of sorting, interpretation, criticism etc. See, Gideon Ofrat, “The Battle between Light and Darkness,” http://gideonofrat.wordpress.com [Hebrew].

3. Assaf Sagiv, “The Magician of Ljubljana: The Totalitarian Dreams of Slavoj Žižek,” Azure 22 (Autumn 2005); see: http://www.azure.org.il/article.php?id=165.

4. Slavoj Žižek, The Puppet and the Dwarf: The Perverse Core of Christianity (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2003).

5. For an elaboration see: Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, trans. J.A. Underwood (London: Penguin, 2008); Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Sheila Faria Glaser (Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1994).

* Ofer Yitzhak, Composition A, 1970s, iron, 48x30x30 cm; Yitzhak Lerer, Composition I, 1970s, olive wood, 40×25.5×16 cm; Joseph Constant, Bird, 1970s, wood, 22x12x50 cm

** Orly Sever, Site-Specific Spatial Installation, 2011, mixed media

*** Iva Kafri, Site-Specific Ceiling Installation, 2011, plastic and paint

**** Mordechai Gumpel, mosaic walls at Yad Labanim Museum, Petach Tikva, 1966-67