Living Zones

Curators: Dr. Irena Gordon, Danielle Tzadka-Cohen, A.J. Weissbard

15/12/2022 -

29/04/2023

Image: From Tomer Sapir’s Exhibition

Peter Jacob Maltz, Tomer Sapir, Alexandra Zuckerman, Maya Cohen Levy, Ami Raviv, Eliran Dahan, Dina Goldstein, and a tribute to Gil Alkabetz

Eight artists present a cluster of solo exhibitions, offering interpretations of the elusive space of the present. Perplexity and quandaries, inundation and anxiety, magic and horror blend and fuse in each of the exhibitions, raising questions about the consciousness of life in a reality divided between physical-material and digital-virtual existence.

The exhibition cluster shifts from stained-glass, artist books, and sculpture to video, animation, and cinema; from internet and artificial intelligence to oil or pastel paintings and paper cutouts. Independently, each exhibition explores the possibility of suspension, of lingering within things, seeing them, feeling them, and formulating their aesthetic, social, and moral significance.

Peter Jacob Maltz is a chronicler, an artist, and a visual pilgrim who makes his way through the present reality of individual life with a broad historical consciousness. In his array of works, Maltz unfolds his personal experiences, set in the context of a large experience that encapsulates past and future. The ars-poetical principle underlying the exhibition calls for passion for the work of art, for art as a powerful tool for change, and the museum as a transformative space that summons an encounter of suspension and lingering, of questions without answers.

“Why is the sky blue? “is a frequently asked question in Google’s search engine—one of nine common, existential-philosophical or practical-banal, questions sampled by Maltz from Google, where they are answered by a disembodied digital algorithm. The recognition of the human need to ask questions and receive quick answers is the driving force behind the exhibition. Maltz strives to reclaim the intimate and personal, the imaginary and empirical, from anonymous and statistical, rational, and economic realms.

The three parts of the exhibition outline a return from the realms of the virtual world to art’s concrete, material, and formal spaces, while exploring the modernist-geometric nature of the Museum’s windows, the entrance foyer, and the space adjacent to it. Maltz replaces the computer or mobile phone screens with the physical exhibition spaces, and surfing the web—with a journey through the Museum, which offers a reflection on the mystery hidden in the ordinary and incidental.

The first part welcomes visitors coming into the Museum’s open-air entrance concourse. The eponymous work Why is the Sky Blue is installed on the outside against 17 windows above the entrance. Suggestive of stained-glass windows, the work unfolds a personal struggle between life and death during a serious illness that attacked the artist’s son. It is an allegorical journey, which requires one to walk along the façade and observe the building from near and far, while leading to a lengthy experience and refusing a quick glance.

The second part welcomes those entering the Museum with a large relief entitled What to watch—another question addressed to Google and answered with recommendations on TV programs. The question prompts Maltz to reflect on it in an artistic context: The relief consists of sculpted elements, copied from still-life items kept in a storeroom of the Visual Arts Stream at Thelma Yellin High School, which Maltz heads. The relief’s constituent elements were created from papier mâché, prepared from the students’ abandoned still-life drawings, whose reuse acts as a conservation of creative energy. One of the inspirations for the relief was Maltz’s own teacher, Pesach Slabosky, who passed away in 2019.

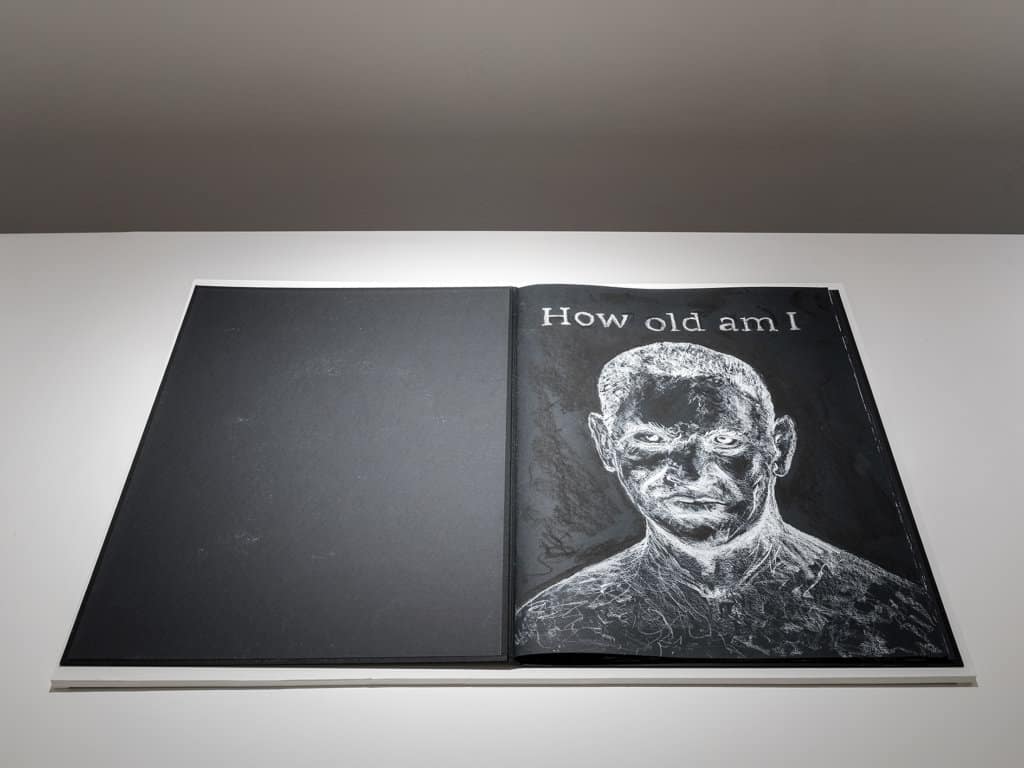

The third part is presented in the elongated space on the right, where books created by the artist are offered for browsing. These books address additional Google questions, such as “What time is it?” From this Maltz departs to create dizzying, highly expressive pictorial manifestations, both colorful and monochromatic, ranging from psychedelia and symbolism to expressionism and pop art, and from realism to caricature. The questions are the driving force behind the books’ artistic creativity, inspiring their overflowing materiality and intensity of color and imagery. Visitors are invited to browse the worlds evoked by the questions, without answers. It is an invitation to closeness and contact, to exposure and sharing, and above all—an invitation to drift into other, extraordinary realms, some harsh and some dreamy.

On an autumnal Friday morning, about four years ago, when he was walking his twin children to school, Tomer Sapir’s daughter, Tamara, asked: “But why do I hear the crickets, it’s morning? ” The question sounded to him like the vision of a prophetess who identified a disruption in nature, and echoed a dream he once had, in which he was walking in the pale light of dawn on the outskirts of a ruined city, amid dogfight arenas, the remains of bonfires, blood stains, chains, and dog carcasses. Farther along the way to school, the twins found an oddly-shaped leaf on the ground, with “evil eyes” created by a disease that gnawed on the plant.

This is the beginning and end of an apocalyptic cinematic scene installed by Sapir in the museum, recounting a sin from the past that trickles into a future mythology. The various parts of the cinematic installation—”The Prophetess’s Dream,” “The Warrior’s Training,” “The Ancient Sin, the Curse, and the Victim,” “The 20th Century,” “Invaders,” “The Father’s Dream”—are embodied in different media—video, photography, sculpture, and text—to form a temporal and spatial process.

The ancient sin, which forms a point of departure for the installation, is rooted in the disturbance that occurred in nature—a vague riddle that is not fully understood, but manifests itself as the refusal of mankind, as individuals and as a collective, to take responsibility for the climatic-ecological crisis and the moral-ethical crisis, and for their environmental, social, economic, and political repercussions felt today.

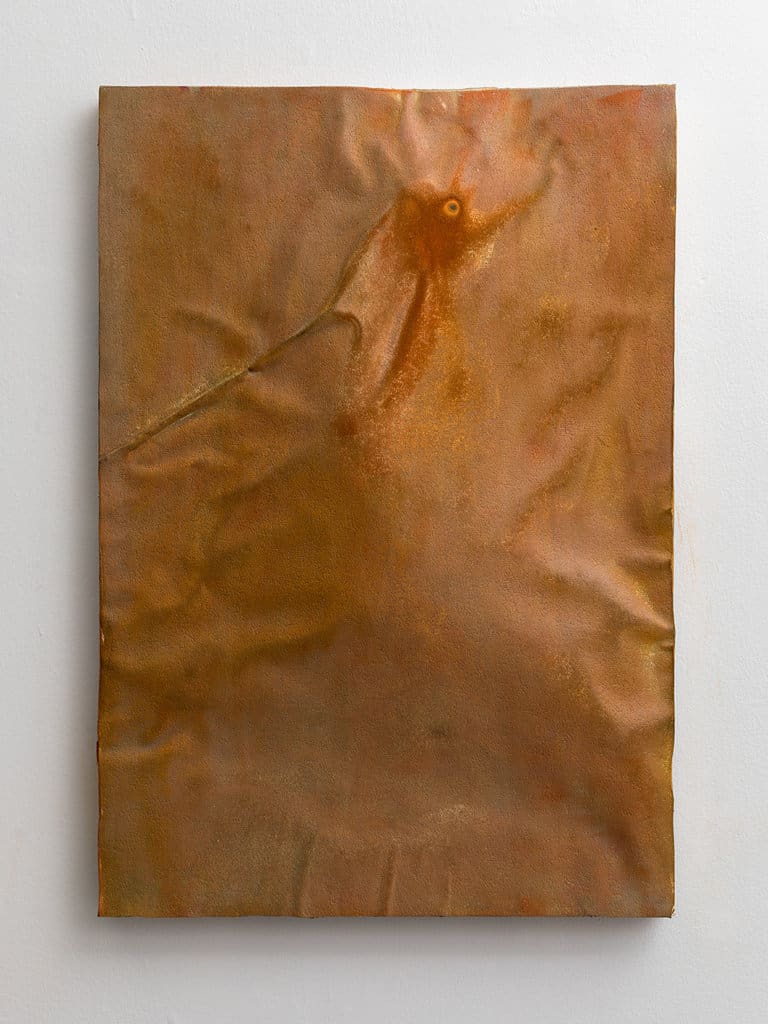

Sapir creates an emergency environment of disaster and survival, which swings between scientific truth and fiction, and between the symbolic-mythical and the scholarly. It is centered on a large makeshift structure, a tent of sorts, a camp or a temporary house made of a combination of organic and synthetic materials: a sheet of dried and manipulated leaves, a sheet of transparent plastic (which Tamara painted and decorated with haberdashery products), an aluminum sheet, and Mylar blankets taken from survival kits. Viewers are invited to enter, sit on cushions, and watch a two-channel video projection: one channel features the son, Nimrod, practicing capoeira with his mentor, Marcelo Oliveira, and the other shows Tamara talking about various mysterious events, including an apocalyptic dream she had.

The video blends personal photographs from Sapir’s trip as a child to alligator-infested swamps in the United States, and from animated and nature films he shot, with documentation of the physical works on view in the gallery: the sheet of leaves, two large sculptures of what seem like mythical creatures, skeletons that were resurrected and became mesmerizing and terrifying presences, remnants of the dog fights, and the inscription: “Moving to a Friendly Territory.” The viewers move between the corporeality of the exhibition space and the material exhibits in it, and their incarnations in the screened video work. Via these transitions, the concepts of the ancient sin, the curse, and the victim are tied together and construed in the intermediate space between the personal-biographical and the universal, the documentary and the speculative. Together they spawn an allegorical treatise on the future of humanity, closely tied to the intimate family unit and to an emotional pendulum swinging between pain and anger, longing and anxiety, guilt and love, compassion, trust, and security.

The series Color Cuts originated in the technique. Using soft pastel chalks in shades of red, purple, yellow, brown, green, and blue, Alexandra Zuckerman creates quasi-uniform spaces that appear as though they were done mechanically, but, in fact, they are the result of a long, meticulous manual process. Each drawing has its own color and pattern, which in some cases is clearly visible and in others virtually disappears against the backdrop of the uniform rectangularity of the painted area. The cuts were inspired by “Burda” sewing patterns and created using tailors’ measuring tapes, in continuation of a previous series which was based on embroidery manuals.

The guiding principle of the series (parts of which are presented in this exhibition) is reduction, limitations, or constraints: using a fixed-sized paper surface, filling the area with repeated application of pastel chalks, within strict borders determined by a large stencil. Due to the dry quality of the pastel chalks, their strokes on the paper—manually covering an area in “slow motion”—generate a layer of color that appears to have been spread above, as the encounter with the white paper margins creates the appearance of a print. Only one color is applied to each sheet, and the composition is created in the space in-between the drawings. Each drawing affects the adjacent drawings, and at the same time it is affected by and transformed in relation to them, revealing an interplay between the white margins of the drawings, arranged side by side in the space in one possible configuration out of an almost infinite potential of dialogic combinations.

The work within this formal structure avoids any representation or image, explicit or implicit. The series thus continues the modernist tradition of non-figurative abstraction, but carries a sensuous, soft, dreamy sculptural quality. Zuckerman’s colorful spaces call one to experience “existence,” as an expansion of time and place that may be sensed through the subtle changes and deviations in the hues and cutting of the surfaces, which at first glance appear uniform, but upon a closer look surrender discernible movement.

The drawings surround the viewer and require both focused and spread out observation. Each color materiality leads to different scenic and mental realms, while the varying geometric subtractions transform the drawings into sculptural-architectural elements. The work’s Hebrew title, Yamim, is the plural form of both sea and day—a watery movement that embeds time and alludes to the absent-present representation activated by the painterly planes, which keep on metamorphosing within our consciousness.

In Maya Cohen Levy’s series of monumental paintings, rocky fields spread out, surrounding the viewer, and inviting one to step inside—to wander across the painting’s ground, to trace the brush lanes, to follow the changing layers, the images of floating stones and mounds of twigs. These are bare, exposed summer fields, in which Cohen Levy captures refractions of light, gaps that form and disappear, deceptive instances of surface and depth.

The body of the painting engulfs the viewer’s body with sights that are drawn from reality, from local landscapes of the here-and-now. The gaze is constantly, stubbornly, turned downward, mapping the earth and its endless expanses, at times in close-up, at others from a distance. In all the paintings, the gaze is filled to the brim with earth, to the very edge of the entire canvas, encompassing consciousness.

Cohen Levy walks in nature, draws, photographs, and collects materials, returning to the studio with their sensory memory. She begins by drawing in charcoal and liquid acrylic, then applies layers upon layers of oil paints, creating fields of reddish-yellowish hues, but also ones of bluish and purplish earth tones. Here and there, a shadow can be seen passing over; sometimes the soil is very thick, and sometimes—it crumbles. The initial traces are not erased, but rather become part of the painterly fabric. The rhythms of the paint strokes coalesce to create changing arrays of the things called “earth,” “stone,” “field—”representations attesting to mutability, to a materiality that is not fixed. In the process, the stones turn into clouds and water shimmers, under the harshness of the scorching summer sunlight.

Cohen Levy channels observation to a terra cognita, the familiar territory of local landscapes imprinted within her, insisting that we linger in front of it. When the gaze rises slightly to a piece of sky, in one of the smaller paintings (Border), it is accompanied by a little human figure and a barbed wire fence. She seeks the traces of what has been, and at the same time generates a new consciousness. Her painting may be likened to a remembering space and a living entity, as the outcome of the incarnations of the earth imagery in the history of art and as a singular occurrence here and now; as an abstract representation and a breathing body.

Ami Raviv relies on the features of one of the Museum’s corridor spaces as a point of depature, transforming it into a metaphor for the human condition. He marks the territory and emphasizes its narrow, low structure, divides it, and installs obstacles and constraints within it and in relation to it. Three partitions, somewhat like revolving doors, stop the movement built into the space, whose purpose is passage between two doorways. While the eyes try to capture the horizon, one’s breath is taken away, and the body tries to advance, but bumps into things, is halted, and must digest the disappointment innate to the illusionary possibility of moving forward.

The space thus becomes one minimalist-conceptual sculpture, whose divisions into vertical planes produce horizontal planes. On the space’s walls Raviv installs paintings-sculptures, which echo topographical models or anthropomorphic landscapes, created with a unique technique he has been using for years: he draws the projection of his body on industrial wood, removes it from these surfaces with a chisel, and wraps them in linoleum. On the linoleum he paints monochromatic color fields reminiscent of landscapes of earth and sky at dusk, or perhaps, the writhing, struggling body and its bleeding wounds.

In the current exhibition these paintings-sculptures are not only installed on the walls, but also function as partitioning surfaces, which now invoke the closed “gates of heaven.” Holding a promise, the partitions allude to the bronze reliefs by Italian Renaissance artist Lorenzo Ghiberti on the doors of the Florence Baptistery, and at the same time—to the closed gate in Kafka’s story “Before the Law.” Raviv thus points out the limitations of physical and mental freedom, the means of power and control, and the external and internal factors that threaten human freedom.

Consisting of sculptural elements and digital works, Eliran Dahan’s installation raises quandaries about the effectiveness of present-day therapy and means of self-care. Images originating in Internet culture and manipulated with 3D software and artificial intelligence, are displayed alongside inanimate objects endowed with human qualities, placing an ironic mirror before them. The entire array introduces the illusion of recovery and realization of potential. The magic touch of code language reveals and reinforces the essence of the material, and yet, in their algorithmic elusiveness, the works remain voided and hard to grasp. In their emptied state they converge into a critical comment about contemporary reality.

A safety orange-colored table shaped like the Greek letter φ (lowercase phi) supplemented with a minus sign (−φ), which in Lacanian jargon indicates castration (minus phallus), is installed in the center of the space. The table serves as a toolbox for storing survival essentials (Everyday Carry, EDC), and is embedded with items that symbolize barren use. Next to the table is a fountain made of Neti pots alongside stainless steel constructions and white noise machines used for relaxation and concentration, “masquerading” as watchdogs; scattered throughout the space are challenge coins and key tags indicating membership in groups and associations that offer rehab, redemption, belonging, and status.

Even the title of the installation, Just for Today, is a well-known mantra in the ”12 steps” protocol of support groups such as Narcotics Anonymous. The slogan promises the patient a day without fears, in which he is protected by guidelines that lead him to himself; one more day when he will experience a life without dependency and live in the present.

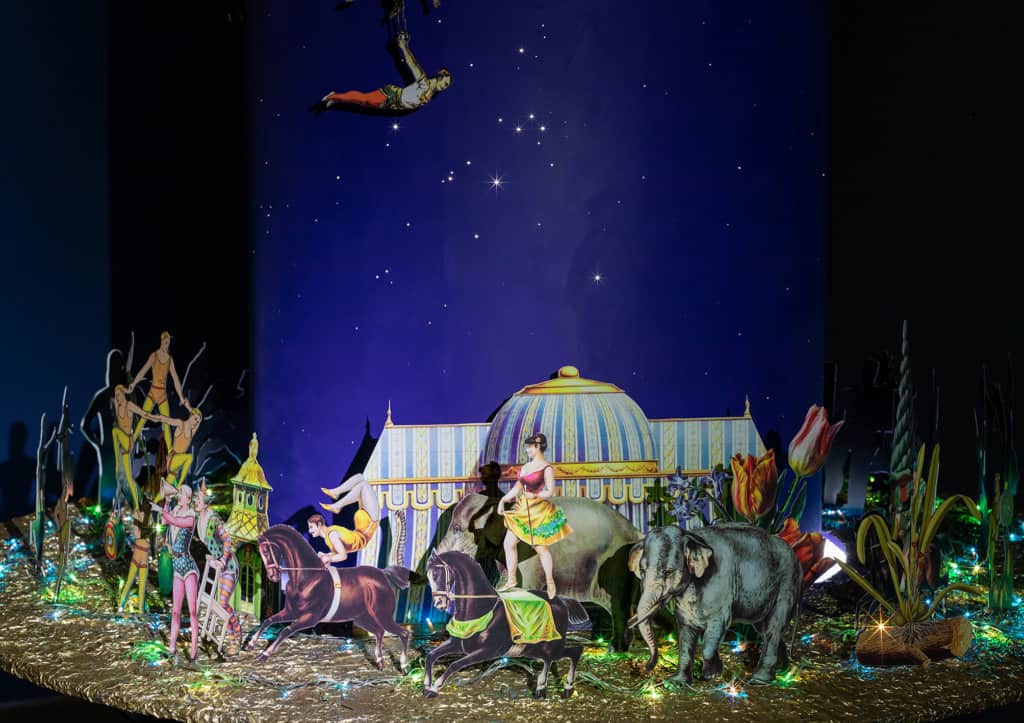

We are bombarded by more and more images everyday as our relationship with the world is increasingly dominated by the omnipresent planar universe of screens. Multi-disciplinary artist Dina Goldstein invites us to reconsider our understanding of the flat second dimension by coaxing it into our three-dimensional reality and giving it new life within the fourth-dimensional landscape of time. Selecting and collecting imagery from a sea of cultural references throughout history, plucking them from their original context, and eventually weaving these images into new narratives, Goldstein carefully curates aesthetic experiences by leading us on a journey through wild and unpredictable landscapes via her own figurative and sometimes literal lens. In her steady hand, her camera becomes our guide as we travel through her improbable and amusing panoramas. Persuaded by the scale in her art, the viewer becomes a new kind of observer, shrinking down like V.F. Odoevsky’s Misha into his snuffbox or falling like Lewis Carroll’s Alice through the looking glass, down into the art itself.

Employing crafting techniques we recognize from our own childhood, paper cut-outs and the like, claiming and configuring imagery from classical art, but also evoking sophisticated Victorian “toy machines,” Goldstein animates static images by both manipulation and cinematography. These techniques engage and delight us while simultaneously freeing us from the mundane visual narratives that plague our modern day fast paced commercial and purposeful world. Part collage, part sculpture, part animation, part puppetry, part video art, part performance, and part magic, Goldstein sparks and primes our imagination. Through simple paper figures carefully juxtaposed, lit, manipulated, and frequently filmed, she manufactures dreams.

Acts of Magic is a celebration of Dina Goldstein’s work but also of her technique and approach. The visitor will find her treasures in every corner of the space: tiny theater dioramas, a floor-to-ceiling paper cutout installation (In My Dream), collages in light boxes, and even a miniature video work accessed only by viewfinder. Some of the works, such as The Spring I and The Spring II, offer us the chance to see different states/phases of her work as the artist re-interprets her own medium in both a staged maquette and light box. Acts of Magic is also the title of a new installation in the rear of the exhibition, encouraging the viewer to consider the work much like the artist does herself, moving around, through it, and amongst the characters and their unique world, crafting a personal experience where we are invited to illuminate, literally, our own experience with the work.

Acts of Magic bids us reconnect with the joy and wonder of which we so often lose sight.

A collection of animated films by animator, illustrator, and cartoonist

Gil Alkabetz, who passed away this year at the age of 65

Artistic advisor: Nurit Israeli

Gil Alkabetz, one of the top Israeli animation artists, created the animated clips for the German film Run Lola Run (1998), and award-winning short films such as Bitzbutz, Rubicon, and Morir de Amor, among many other works. He was born in Kibbutz Mashabei Sadeh, studied graphic design at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, Jerusalem, and in the last three decades lived in Stuttgart, Germany, where he was a professor of animation at Filmuniversität Babelsberg Konrad Wolf, and created films in an independent studio he founded with his partner, Nurit Israeli.

Always addressing the human condition, his work is characterized by a clean, simple line that settles for the necessary minimum, and a humorous gaze wrapped in a veil of melancholy and absurd. Already in Bitzbutz, his first film as a student at Bezalel, Alkabetz explored the principles of reduction while focusing on a white background, against or from which fantasy is born. In Rubicon—an allegory about the attempts to mediate the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, centered on the theoretical riddle of how a wolf, a sheep, and a cabbage can cross a river without the wolf eating the sheep and the sheep eating the cabbage—the space of occurrence is white, and the river itself is nowhere to be seen. Similarly, Swamp—an allegory about war—emerges as a beautiful drawing against the white void.

In other works, Alkabetz focused on reducing the number of images, until in The Da Vinci Time-Code he reached a single image — Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper — which he broke down into fragments and reassembled in a rapid montage, pointing to the foundations of painting and cinema, and the possible transitions between them. The one frame encapsulates an entire narrative or a whole world, as in painting, illustration, and caricature, unlike the sequence of images in cinema and animation. Under the influence of the fast-flowing, rapidly-changing images typical of the Internet and the digital world, and the multitude of platforms that encourage brief, concise expression, Alkabetz created works that radicalized the temporal reduction down to a minimum of one second, as in Bedtime Copynight and Catduck.

From the very outset, Alkabetz always preferred 2D animation based on drawing and illustration, practices in which he engaged simultaneously throughout his career. He believed that 2D animation posed a greater challenge in representing reality, and therefore yielded a broader scope of ideas and possibilities. In the case of Beseder (Good and Better), a music video he created for Tova Gertner’s song by that name, these were drawings he created regularly, day in day out, without intending to turn them into animation. The magic of the movement that he breathed into them and the resulting sequence infused the work with life.

In his work, Alkabetz sought the image’s moment of discovery, the movement or story that introduce a new order. In an essay entitled “Animation and the Art of Limitation,” he wrote: “The prevalent image of the art of animation among the general public is that it is an art form, in which everything is possible, since there is nothing tangible in it to limit the artist’s imagination. […] Precisely because of this, one of the animator’s basic tasks is to create a universe that has its own internal logic from the countless possibilities at his disposal, even if that universe is fantastic and negates common sense.”