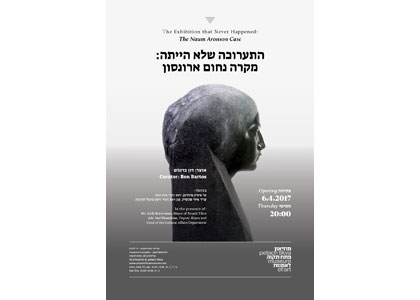

The Exhibition that Never Happened: The Naum Aronson Case

Curator: Ron Bartos

06/04/2017 -

05/08/2017

While stored in the cellars of the Musée du Louvre in Paris, Naum Aronson’s sculptures found themselves in limbo. With the outbreak of the Second World War and the German occupation of Paris in 1940, the prominent Jewish sculptor escaped to the United States. Before leaving, he entrusted his artworks to the Louvre Museum – a few of his sculptures that were displayed in the Museum in the past, and others from his atelier, which he had to clear. At this point in history, the sculptures’ future hanged in the balance between the horror of “hell” and the salvation of “heaven”: the prospect of “hell” threatened to doom the works to the fate that befell many other art treasures plundered by the Nazis. On the other hand, the prospect of “heaven” could have ushered in a bright reality for Aronson’s sculptures, the realization of which would have been as simple as being brought from the cellars to the galleries floor, and displayed in the world’s most famous museum. As fate would have it, it was “hell” that the unfolding of history conferred on Aronson and his art.

Naum Aronson’s sculptures were confiscated by the Germans, along with countless other artworks from the Louvre’s collection, and loaded onto a train headed towards Berlin. Not eager to complete this task, the French rail workers decided to prevent the looting of these masterpieces. And so, they “traveled” with the train across France rather than make their way to Germany, and at the opportune moment, handed its contents to the Resistance in the countryside. The Jewish members of the Resistance transferred Aronson’s sculptures to the care of a children’s home in the French village Les Andelys, where they remained after the War. In 1952, deputy mayor of Petach Tikva David Tabachnick joined a delegation of the Zionist Organization in a visit to that children’s home, which by then had already housed the orphans of the War and was named after Aronson. There, Tabachnick was surprised to discover Aronson’s sculptures scattered around the courtyard, where the children had put them to use as targets in stone throwing games. Upon his return, he arranged for the sculptures to be brought to Israel and added to the art collection of Yad Labanim Museum, today’s Petach Tikva Museum of Art.

The Exhibition that Never Happened: the Naum Aronson Case, wishes to turn back time to offer a late redemption of sorts to Naum Aronson’s sculptures, and imagine their return to the Louvre – the “heaven” that was prevented from them by history.

The Museum’s collection gallery was transformed into the semblance of the Louvre’s sculpture galleries, with a display dedicated to the works of the Jewish sculptor Naum Aronson. Alongside this revisit of the Parisian museum and the middle of the 20th century, “the Louvre” at Petach Tikva Museum of Art is also a temporary and imaginary Israeli branch of the famed museum, at a time when the Louvre in Paris acts as the flagship branch of museums that bear its brand name. Thus, in 2012, Louvre-Lens was inaugurated in the mining town in the north of France, and a new extensive branch has just opened in Abu Dhabi (the emirate will pay France almost 1.5 billion dollars for the use of the brand name and loan of artworks from the Museum’s collection, which includes artifacts and artworks originating in the area to which they now return). Obvious differences aside, and keeping in mind the real fate that befell Naum Aronson’s works, the imaginary Louvre in Petach Tikva is also informed by the contemporary restitution of artworks plundered by the Nazis. This exhibition therefore constitutes a symbolic return of Aronson’s sculptures to the Louvre Museum and to their French context, while presenting them in the Israeli museum that saved them from destruction and oblivion.

History cannot be re-written, but alongside the opportunity to present Aronson’s sculptures at the Museum’s collection gallery, this exhibition can also serve as a platform for reflection on questions such as: what would have been the sculptures’ artistic value if they were not plundered by the Nazis? Or alternatively, what would have been their cultural significance if they were displayed in the Louvre – one floor above their place of storage? What would have been the historical significance to Jewish culture for an artist like Aronson to gain such recognition? What is the nature of the canonization processes that doomed Aronson and his sculptures to oblivion, while they could have, perhaps, grant him fame? And to follow this line of thought, what would have been Aronson’s status in the history of art (including Jewish-Israeli art) if the historical verdict would have been a different one? And venturing beyond Aronson’s case, we will ask what other artists and artworks disappeared under the dark shadow cast by the Nazi regime (and by regimes and governments in general) on art and culture, and what could have been their fate if the course of history had been different?

The dormant potential that was embodied in the works when they were stored in the cellars of the Louvre, is realized now with a symbolic act of redemption: taking them from the recesses of the cultural subconscious (the museum’s cellars) to the consciousness (the display); extricating them from the “death” of the storeroom (the correspondence between the museum and its storerooms and a graveyard is a known and familiar one) for a second life; and examining the fictional possibility of “heaven” instead of the factual historical “hell.”