Solar Stain Eliahou Eric Bokobza

Curator: Drorit Gur Arie

15/09/2016 -

11/03/2017

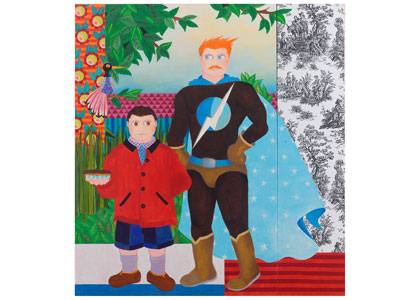

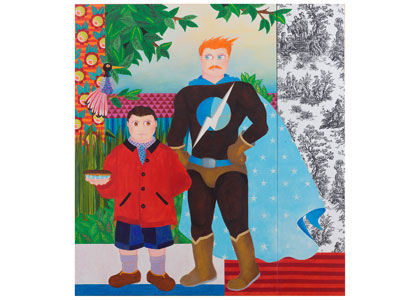

Eliahou Eric Bokobza’s work draws on the discrepancy between the decorative, seductive appearance of a childlike painting and a penetrating gaze into the bowels of Israeli culture, as if he were sticking a pin in the balloon of hegemony and canon ingredients. Bokobza’s field of reference is the image depository of Zionism and Eretz-Israeli art—hackneyed objects and depictions which he empties of their original meaning and introduces into scenes of non-belonging and social detachment. Vis-à-vis all these, Bokobza introduces a counter-memory—a memory practice which negates the official history, reviving and presenting forgotten, repressed or silenced histories. His opposing image of the world undermines-contradicts, at times also expands-complements, the convention—whether by including Arabs in depictions of the place a-la Nahum Gutman, or via reconstitution of Boris Schatz’s artistic pantheon to also include artists of Mizrahi origin, those who were excluded from it in the “Bezalel” days by their labeling as “artisans.” In the current exhibition Bokobza proposes a counter-memory to the heritage of the Jewish and Eretz-Israeli artists of the School of Paris (École de Paris), who streamed to this center of Western art and modernism. At the same time, he completes his own memory image, as he juxtaposes the sweet memories of his Parisian childhood with the perception of reality of the adult man who was subject to racial prejudice and experienced the assimilation difficulties of the North Africans, in both France and Israel, first hand.

While in the past Bokobza relied on the safety net of art history and used fictive relatives, who were inserted next to his eternal doppelganger, to reconcile the identity conflicts between East and West, this time his alter-ego emerges in the figure of the Parisian boy Eric, aided by attributes deeply rooted in French culture and known mainly to the locals. The journey, which consists of memory fragments and a vivid imagination, relies on his biography, abruptly unfolding the reason for leaving the city: “Eric is off to fetch the sun,” the teacher explained his sudden departure in the middle of the school year. The teacher even produced a traditional French puppet show (“Guignol”) in which Bokobza played himself as a hand puppet holding the wheel of the sun (for the “Levant” is where the sun rises and sets).

This jolting painterly process, like a return to the lost Paradise, brings to the fore absence and a loss of innocence, conveying a sense of foreignness in a place, everyplace. The return home is thus accompanied by the adult consciousness of a protagonist already imprinted with an Odyssean scar, and like any late return—it is doomed to fail. Although amiable, protective friends and tempting whipped creams join the journey, the distance unveils Paradise, in the image of the Parisian park, as a site of evil bubbling under the warm childhood blanket.

An animated installation that forms the heart of the show pursues the experience of watching the Guignol—an outdoor hand puppet show appealing to children and adults alike. The play featured here reawakens the circumstances of his departure from the French capital which the teacher ignored in her farewell play. Bokobza’s childhood past in the City of Light is once again tainted with the shadows of anti-Semitism, which remind the play’s protagonist—who is beaten by all the other characters—the origin of his family, and the derogatory name for people of North-African origin in France: “pieds-noirs” (black feet).

Paintings by Zvi Shorr (1898–1979) from the collection of Petach Tikva Museum of Art, portraying landscapes of Paris, Jaffa, and the Yad Labanim Park next to the Museum, function as backdrop to the puppet show and as part of the exhibition. Two routes of immigration, back and forth, thus function in the exhibition along the Israel-Paris axis, since Shorr too—like many other Eretz-Israeli artists—left for Paris in the second half of the 1930s, and became closely affiliated with the circle of Jewish artists in the city, who strove to be a link in the chain of French modernism, but were classified as “strangers,” “outsiders,” “stateless,” or “expatriates.” Shorr’s gloomy and empty Paris, in dark green-brown hues, is far removed from the colorful and lively city depicted by Bokobza, who observes it not as a passerby, but as a native, presenting it as a cluster of geometric shapes in vivid colors.